|

How's your Aerobic Fitness?

MAF Test (Maximal Aerobic Function Test): Perform this test every 3 to 6 months. It should steadily improve as your work capacity and aerobic fitness goes up. If it is declining, then your workload may be too high or you are not recovering well. Resting Heart Rate Average of <60-70 beats per minute (BPM)--taken first thing in the morning. This takes about 2-3 weeks to get accurate baseline data as heart rate will fluctuate day-to-day a few beats per minute. However, if you are +/- 7 BPM off of your average, you may be a bit under-recovered or possibly getting sick. Are you strong enough for Interval Training? Have you been strength training consistently for at least 6 months? After an all out effort, does your heart rate drop 30-40 beats in a minute? Some strength standards: Trap Bar Deadlift 1-1.5x bodyweight, 10 Pushups, 1 chin-up for females/5 reps for males (as a baseline minimum). Strength should improve over time, as well. How's your Stress profile? Are you sleeping 7-9 hours a night? Do you wake up frequently in the middle of the night? How is your perceived level of stress? Low, Med, High? Have you had a recent change in your lifestyle? (i.e.-recent divorce, job promotion, recently unemployed, etc) Do you have a releasing practice? (meditation, quiet walks, spending time with friends, listening to music, etc) ***When in doubt, focus on staying away from the middle (anaerobic/glycolytic) and prioritize getting stronger, improving aerobic health, and finding ways to unplug and recover from stress. Resources The Big Book of Health and Fitness by Dr. Phil Maffetone Easy Strength by Pavel Tsatsouline and Dan John Neuroscience for Coaches by Amy Brann All About Cortisol by Ryan Andrews from Precision Nutrition

0 Comments

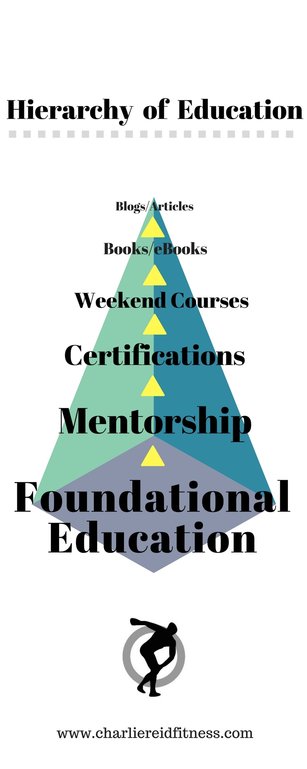

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the state of education in the fitness and wellness industry. It is an industry that is growing rapidly, which brews up a lot of excitement and opportunity; however, with very little regulation and quality control, this can have negative consequences and much frustration as up-and-coming professionals navigate the rocky landscape of education and experience. This blog serves to provide a simplistic hierarchy of needs for those looking to better themselves through education and practice. This is how I evaluate my own educational needs and how I keep my own biases in check. For example, if you spend much of your educational budget on eBooks and reading blog posts, but have never actually read a science textbook or taken a basic course in biology, your education is a bit lopsided. All of these categories of education have their place, but they need to be balanced with their respective layers. When in doubt, stick to the base of the pyramid.

Critical Thinking/Reasoning I start with this category as the foundation of the educational hierarchy, because it is not just a category, it is a way of engaging with the world—a way to seek truth or, at the very least, get as close to it as possible. It is also not a quality that is emphasized enough in our formal education system. Due to the time needed, the constraints of both public and private education, Critical thinking often gets overshadowed by rote memorization, standardized testing, and linear thinking. Critical thinking and reasoning is a skill that takes practice and time. Like a good chef’s knife, it needs to be sharpened and honed constantly. Our mind constantly makes errors and our own biases affect the decisions we make all the time. The best tool you can utilize is the ability to thinking clearly, rationally, and critically. Here are some resources I have found helpful for getting started.

Foundational Education One of the biggest problems in the fitness industry is that we have a low barrier to entry. You can be hairdresser one day and after a weekend certification, you can call yourself a Personal Trainer. Actually, if you can convince someone to let you purchase a liability insurance policy, you don’t even really need a certification. Sad, but true. Nevertheless, one of the problems is a lack of foundational education. This could be remedied by a quality undergraduate education, however, I understand that not everyone has an undergraduate degree in something like Kinesiology or Exercise Physiology. The good news is that many universities now offer courses online for free! The information is there, you just have to set aside the time to assimilate the info. The biggest reason why I stress foundational education is that it allows you to become a better problem solver when you start working with people AND gives you a better ‘bullshit filter’ when it comes to evaluating the quality of exercise and nutrition programs, exercise equipment, supplements, and more. The more educated you are, the more time and energy you can save by ignoring as many charlatans and misinformed (although sometimes well-meaning) ‘experts’ out there.

Looks a lot like a liberal arts undergraduate education, doesn’t it? I’m not saying you have to go back to college, but certainly spending time reading and assimilating basic science textbooks and engaging with those more educated than you on each topic is a very valuable use of educational time. And my last point on this is that there are a bunch of people i see trying to read research and post PubMed articles, when many of them would be better suited to simply reading textbooks. A lot of questions can be answered not by seeking out research articles, but by reading basic info in textbooks. Mentorship/Internship This is arguably the most valuable investment if you have the opportunity and resources to do so. Seeking mentorship/internship experience is the best way to not only learn, but also practice and assimilate information in real-time. There are those out there that may have plenty of book knowledge, but have a hard time with practical application. Also, the trickiest part about this business is not the acquisition knowledge itself, but working with people and applying this knowledge in the real-world. One of the toughest parts of working with people is that they are human...and human behavior doesn’t fit into neat little boxes. It is only when you have a firm grasp of the material, understanding the principles at a deep level, that you can start to mold and modify those principles to custom-tailor your coaching to the needs of the individual or groups in front of you. Certifications Getting a certification is simply a way to get your foot in the door so you can start working and actually obtain experience. Find a reputable/accredited company and ask your future place of employment what certifications they recognize. This is more about getting a job than it is about knowledge. Good certifications will also provide efficient heuristics and systems to help you to quickly and efficiently manage a full client load, although don’t get too comfortable with simply following the system forever. Evolve your thinking as your experience grows and the industry evolves. Beyond the knowledge obtained, certifications also plug you into a network—a tribe—of like-minded professionals who you can bounce ideas off of, share case studies, and possibly provide a conduit for mentorship/internship and even jobs in the future. When assessing which certifications you should get, start with an honest appraisal of your knowledge and experience and see which holes you need to fill. If you work with the general population, you will need to be an excellent generalist. In my opinion, I think you should spend 5 to 10 years being a great generalist anyway before you specialize (should you want to), but I digress. The three primary categories you will want to assess are: Nutrition: if you work with clients seeking body composition or athletes looking for performance improvements, nutrition is paramount. For those looking to lose weight, the literature is pretty clear that exercise is not that effective for fat loss; therefore nutrition becomes a priority for those looking to lose fat. For athletes, recovery and favorable responses to training are predicated partly on how well they fuel themselves. Strength and Conditioning: Basic S&C principles should be covered in a basic training certification, however, you may also need to seek out additional certifications to deal with special populations or to go more in-depth than what you might obtain in a basic certification. If you work with youth athletes, consider a youth athlete cert, if you work with geriatric populations, consider getting a specialty cert in that. Assessment and Mobility: Especially as we deal with very sedentary people with poor physical literacy, movement quality, and movement capacity, it’s becoming more and more important that we screen and assess people to decide what types of training interventions are going to be appropriate. Having a system to assess joint ranges of motion both actively and passively, basic biomotor abilities and activities of daily living, and performance testing to measure physical capacity based on the needs of the individual or groups that you work with become important. Weekend Courses/Summits Most of these weekend courses and summits are just surface-level educational presentations and glorified sales pitches for higher-level products. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing if you know that going into it. But just know that these types of events are really best suited to get exposure to a myriad of different people, philosophies, and systems. These can also be an excellent place for networking opportunities. Books/eBooks This category is a little tricky because there is a large variance in the quality of different books and ebooks. Thanks to the internet, anyone can publish an eBook which certainly helps the spread of information, but it also means there’s a lot of garbage that comes with it. I will abstain from talking about textbooks, because I consider those part of the ‘foundational education’ category. If you read enough books, you will start to realize that there isn’t always a lot of ‘meat’ to books and certain publishers might require a lot of filler in these books to make the product appear more valuable. You might also come to the realization that many books are re-synthesizing information that is already out there. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing as synthesis allows our thinking to evolve in the face of new evidence, however it can also come with a lot of non-sense. This is where honing your critical thinking will become incredibly valuable. Building a Referral Network This isn't really part of the educational hierarchy, but i figured i'd throw this in for the sake of utility. Having a solid referral network is a great way to not only learn from other professionals, but also to help build your business and help people get better. It certainly takes a village, and the more arrows you have in your quiver, the more you are going to hit the bullseye with helping others improve their health and performance. Nutritionist: I recommend finding a good RD for special populations like diabetics, the morbidly obese (>40 BMI and above), or with other manageable diseases that require a specialist to monitor them. They may also be useful if someone wishes to purse a very low carb or ketogenic diet, which is not within the scope of trainers to prescribe and help manage. Physical Therapist or Chiropractor: Try and find one that understands movement, is an excellent manual therapist, and understands the importance of exercise. If they can’t write a good performance program, they wont understand when to make the hand-off from rehab to performance training. They should also be in favor of a concurrent model, wherein the athlete or client in question will not stop training (unless they are in a full body cast maybe), but will modify as needed to make sure they do not get de-conditioned. If they don’t look like they train or have ever trained, I wouldn’t refer to them. They should also ideally understand YOUR population(s). If you train a lot of golfers, you should ideally find someone that works with a lot of golfers. This isn’t as essential, but it certainly helps. Massage/Manual Therapist: Good Bodyworkers can be hard to find as the good ones are usually booked solid and they also tend to be a very transient bunch--often setting up shop for a bit and then leaving to another city or country. I am constantly seeking out a handful of good Bodyworkers to refer to for clients that I think could benefit from massage services. At the very least, even basic Swedish or Spa massage can be a great addition if the client or athlete is willing to and has the resources (time and money) to get a massage when appropriate. Bloodwork: Basic bloodwork can be obtained from someone’s doctor during a routine physical, however, there are private companies that provide comprehensive bloodwork to help keep an eye on important markers of health like blood cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, inflammatory markers (c-reactive protein), etc. Monitoring this every 6 months to a year can help create a timeline to help manage stressors that may be showing a positive or negative trend over time. This can be a useful tool to guide decision making when it comes to health and fitness interventions. DEXA Tech: For those unfamiliar with DEXA scans, they are the gold standard for measuring bodyfat, muscle, and bone density. Additionally, DEXA scans can tell you where exactly you are gaining and losing fat. This could be important for cardiovascular disease risk (see: gynoid vs android obesity). Third-party companies are popping up in most major cities and I’m sure they will make it out to more rural parts eventually. I recommend a DEXA scan every 6 months to a year as well to monitor changes in body composition which can also help drive better decision making when implementing smarter health and fitness interventions. Sport Coaches: If you work with athletes, either professionally or recreationally, start asking around for the best sport coaches in your area. If you work with a lot of tennis players, try and find the best tennis coaches. If you are a rehab professional, having a good relationship with sport coaches will not only help your business, but it could also help provide you with clues as to whether or not their sport technique might be exacerbating any injuries that your patients are presenting with. For trainers and strength coaches, the sport coach can provide valuable info as to how you can be useful to them in the gym. This can help to compliment the training process and fill in the gaps of development for the athlete in question. I hope this post helps you to funnel your own thinking about how to organize your educational pursuits. And, as always, any suggestions on how to make this better are welcome. As an avid reader and lifelong learner, i'm always looking for ways to maximize retention and help to streamline the learning process. Peter Brown's book Make it Stick is an excellent resource for doing just that.

Here are my notes:

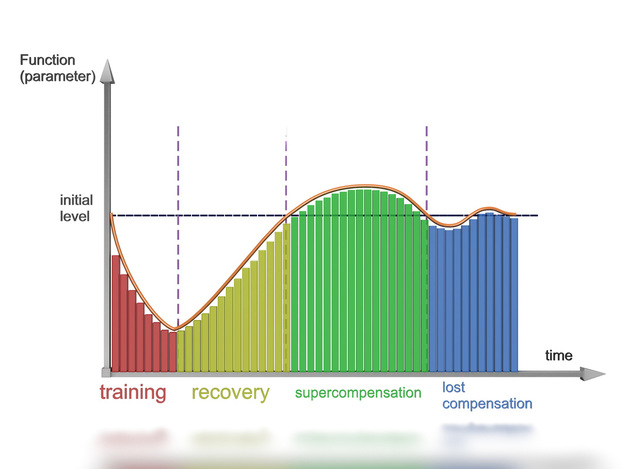

I get a lot of questions from folks asking questions about when and why to stretch. There are many pervasive myths that exist around stretching, but few resources out there helping to dismantle these beliefs and then formulate a framework as to how to apply stretching at the right time. I think if you spend enough time in the literature on stretching and flexibility, the less and less of a fan you will become of static stretching for the goal of increasing usable range of motion. This isn't to say that static stretching doesn't have its place (i personally enjoy relaxed static stretching as a way to wind down at the end of the day or after i've done a hard workout), but i think people can overdo it by stretching too much passively while ignoring more active means of mobility training. I've provided an infographic below in an attempt to deconstruct the three most common reasons why people feel the need to stretch. When you start to really dig into this stuff, you realize that acquiring more mobility is really just a wonderful by-product of intelligent, progressive training. For example, if you feel tight all the time, it may be that you are simply too stressed and doing too much work than you can recover from (as opposed to thinking you are tight because you have structurally "short" muscles that need to be stretched all the time). In this case, yanking on muscles more will likely not fix the problem. Having an understanding of progressive training principles (SAID principle, Specificity, Progressive Overload, etc) and adaptation can help guide us towards increasing range of motion in a safe and systematic way. I find it interesting that we apply progressive training principles to increasing strength or endurance goals, but we forget that increasing one's mobility is an adaptation, as well. It may be a longer, slower adaptation process, but i would argue that it still adheres to basic principles of adaptation just like strength and endurance training does. It is my hope that this infographic will provide more of a birds-eye view of mobility training that will steer us away from the old paradigm of "stretch to loosen, strengthen to tighten". I believe we need to start looking at mobility training through more lenses than just tissue biomechanics. We need to bring in other disciplines from strength&conditioning, psychology, pain neuroscience, motor control, and more. And most importantly, i hope this starts a conversation amongst professionals to keep evolving this concept while putting this stuff into practice. A theory is useless if it can't be applied. Enjoy! References

Drew, MK, & Finch, CF. (2016). The Relationship Between Training Load and Injury, Illness and Soreness: A Systematic and Literature Review. Sports Med. Jun;46(6):861-83. Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, Sørensen H, Kjaer M. A mechanism for altered flexibility in human skeletal muscle .Journal of Physiology. 1996 Nov 15;497 ( Pt 1):291-8. Moseley GL, Hodges PW. Reduced variability of postural strategy prevents normalization of motor changes induced by back pain: a risk factor for chronic trouble? Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006 Apr;120(2):474-6. O'Sullivan K, McAuliffe S, Deburca N. The effects of eccentric training on lower limb flexibility: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012 Sep;46(12):838-45. |

About the AuthorCharlie Reid considers himself an "anti-guru", an educator, and an enthusiast for all things that make humans stronger and more resilient. His pragmatic approach centers around helping others find solutions that are practical, while sifting through all the hype so prevalent on the internet. Archives

April 2017

Categories |